Episode 17: Lessons from Recife

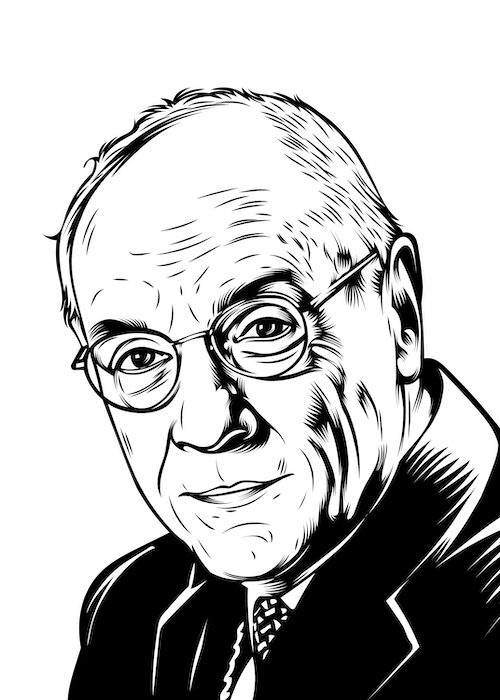

Riordan Roett on America’s Intervention in Brazil

As the United States competes for influence around the globe, and as authoritarianism gains ground in places like Brazil, what will US engagement in Latin America look like? US intervention and influence in the region is nothing new, especially in Brazil, which this week’s guest walks us through. Professor Riordan Roett takes us on his journey as a young Fulbright Scholar living in northeast Brazil during the Cold War, to becoming one of America’s leading experts on the country. Seeing firsthand the consequences of US intervention, Roett argues that Washington should take a more grassroots approach to development support, bolster its diplomatic corps, and invest more in cultural engagement to strengthen ties with the region.

Listen Here: Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Libsyn | Radio Public | Soundcloud | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn | RSS

Riordan Roett is Professor and Director Emeritus of the Latin America Studies Program at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

This podcast episode includes references to the Eurasia Group Foundation, now known as the Institute for Global Affairs.

Show notes:

Marxists Are Organizing Peasants in Brazil (Tad Szulc, New York Times, 1960)

Brazilian Leftist Reports Plan For New Peasant-Worker Bloc (Tad Szulc, New York Times, 1960)

Archival audio:

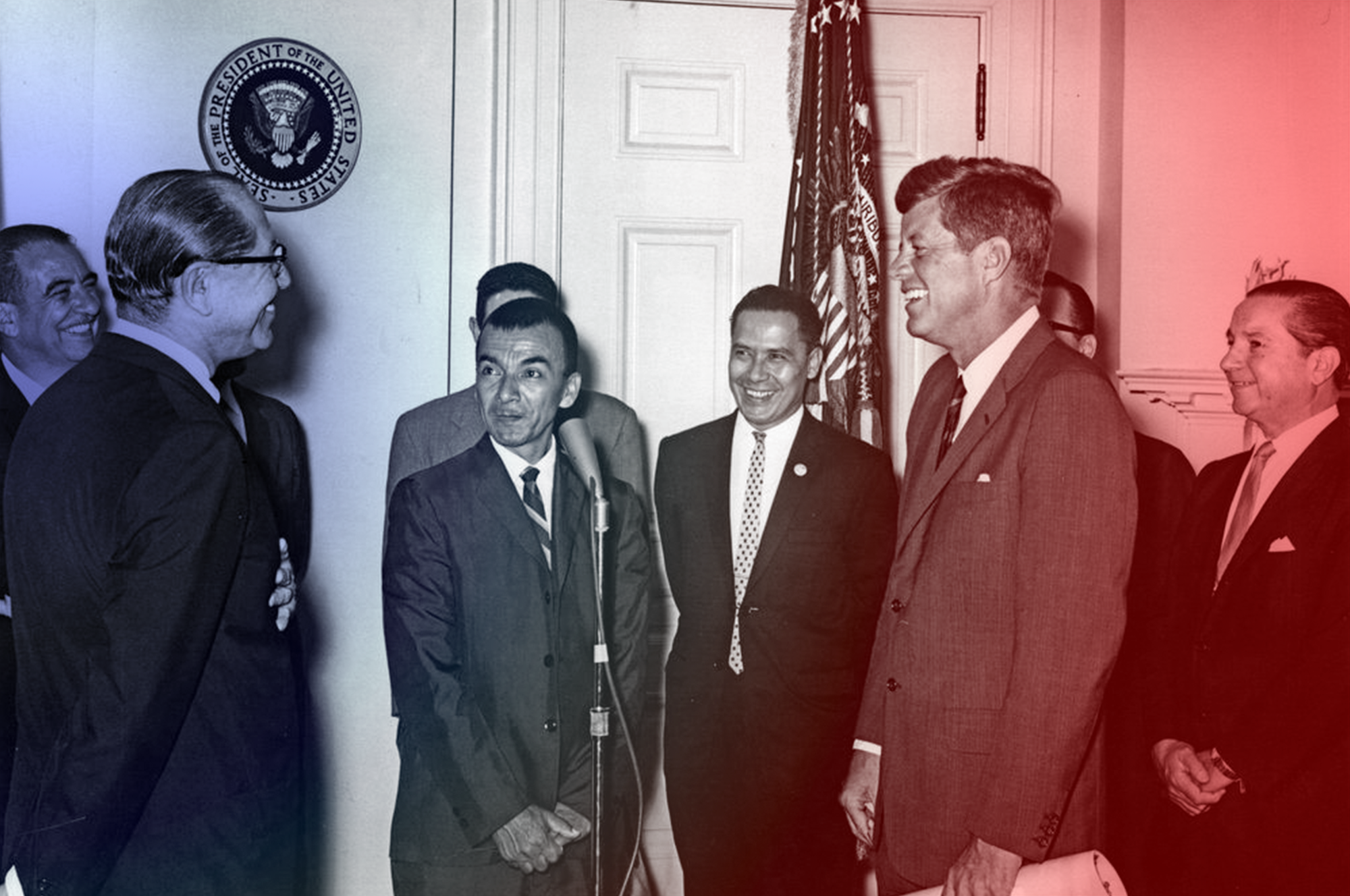

Forging the Alliance - President Kennedy Visits Venezuela and Colombia, December 1961 (Reel America, December 18, 1961)

The 1964 US Backed Coup in Brazil (Benji, January 17, 2020)

Why did Brazil become a military dictatorship in 1964? (Choices Program, August 17, 2021)

Brazil: Goulart Deposed in Coup D'Etat 221726-11 | Footage Farm (footagefarm, November 26, 2013)

Jimmy Carter on Human Rights 1978 (Forquignon History, April 24, 2018)

Rosalynn Carter no Brasil, 1977 (Picilone_, February 8, 2015)

Waging Peace (Carter Center, September 19, 1995)

Transcript:

November 23, 2021

RIORDAN ROETT: Our problem is we think we can shove democracy down people's throats, and that's a glorious trait of both parties. And I think some people in the parties actually believe it. But it's never worked. And, what you got to do is work from the grassroots up.

MARK HANNAH: Welcome to None of the Above, a podcast from the Eurasia Group Foundation. My name is Mark Hannah. Today, I'm delighted to be joined by Riordan Roett. Riordan is a professor and the director emeritus of the Latin American Studies Program at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. From being a young Fulbright scholar in Brazil in the 1960s to being named the diplomatic order of Rio Branco by Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso in 2001, Riordan has had a long and distinguished career as a political scientist and a prolific Latin America scholar.

Today, we dig into U.S.-Brazil relations, America's history of intervention and influence in South and Central America, and more with one of the region's foremost experts.

Riordan, thanks so much for being with us today.

ROETT: A pleasure.

HANNAH: Why Brazil? When you were a young man, or through your career, you focused on different countries—Mexico and through Latin America. But what drew you to that part of the world?

ROETT: I began in Brazil. And when I was finishing my undergraduate degree—I guess my master's degree in Colombia, School of International Affairs—a notice came around saying, “Why don't you apply for a Fulbright?” And I thought, “Well, that sounds interesting. I'll go to Paris or Berlin.” Then I read a series of articles in the New York Times by Tad Szulc about something called the Peasant Leagues in the northeast of Brazil. And so, my buddies and I went to the West End café as we usually did at night and had a couple beers. And we said, “Do I want to go on a Fulbright or not?” The vote was yes—three to zero—I'll go on a Fulbright.

HANNAH: You had a little council—tribunal—of people to help you.

ROETT: Beer drinking buddies, yeah.

So, I went back and said, “Alright, I applied to go to Brazil.” And I thought, “Would it be interesting to go to the northeast of Brazil to Recife—I didn't know where Recife was—and see what this thing is about the Peasant Leagues Tad Szulc was writing about, which I thought was very interesting. As a political scientist, that sounded like fun. So, I applied for a Fulbright to Brazil, and being a smartass graduate student, I thought, “OK, I will not go to Rio de Janeiro. People will think I want to sit on the beach”

HANNAH: Right, with all the other gringos.

ROETT: All my classmates went to Brazil and sat on a beach.

I will go to Recife. And, I talked to Tad Szulc and he said, “You're going to Recife?”

And I said, “Oh yes, Mr. Szulc It’s going to be very exciting.”

He said, “Yeah, write to me about it if you live.”

So, I called back and said, “Thank you very much for the offer. I'll take my chances by going to Brazil.” I got the Fulbright went to Brazil. And so, I flew up to Recife, went to my instituto, got it affiliated. Celso Furtado, a very well-known economist, had become head of the Superintendency for the Development of the Northeast and was working very closely with the Alliance of Progress to change the Northeast. And I thought, “This is not going to end well.” I didn't say that to Celso Furtado.

And I had this really stupid proposal of studying—I don’t know—federalism or something. Nonsense. I went to see him and I said, “Does this make any sense?”

He said “no.”

I said, “What should I be looking at?”

He said, “Why don’t you look at USAID and the Alliance of Progress?”

“OK,” I said, “That sounds interesting.”

I made good friends at the Alliance of Progress office and then began going around interviewing people. And I discovered—because I was leaving Recife on the weekends to go into the interior to talk to people—but no one from the consulate seemed to be going into the interior, which I thought was strange.

So, I went back and said, “This is what I found.”

And I get that marvelous rolling of the eyes kind of thing: “Oh, Roett is here again with his stories about the peasants.” So, I thought, wait, this is a very interesting topic. It was my first focus of politics of foreign aid in the Brazilian Northeast.

HANNAH: As someone who knows the region intimately, where did America's investments and interventions in South and Central America—and also in Brazil, specifically—go wrong?

ROETT: As we usually do, we found out in Afghanistan and other countries, throwing money at a problem doesn't solve the problem. We as a country have never quite learned that. We had a huge mission in Recife, filled with people who didn't speak Portuguese, who probably had great technical talents, no question, but if you don't speak Portuguese—I always thought, “Why are we in Afghanistan if you don't speak Pashtun? But what do I know?—Why are you in the northeast of Brazil if you don't speak Portuguese?

As they began spending millions—in those days, millions of dollars is a lot of money—trying to find political allies among the politicians in the Brazilian northeast. And this is when Lincoln Gordon—a very competent but rather conservative ambassador for John F. Kennedy in Rio de Janeiro at the embassy—came up with the idea: “Well, we'll find islands of sanity,” he said. You know what that means?

HANNAH: Islands of people who think like us.

ROETT: As we did in Afghanistan, in Vietnam, in Iraq—we do it all the time.

So, the islands of sanity were all the conservative governors in the northeast of Brazil, so we began pouring money into these states in our election in October of ‘62. And of course, only one conservative won. The rest of the states that had elections at that time where I wasn't state pernambuco elected a very charismatic, left of center—he was called a communist, he was no more of a communist than I was—Miguel Arraes —very interesting fellow—who actually wanted to do something about poverty. Imagine: poverty reduction. He wanted to do something about inequality. The elites didn't like that. And so, Arraes in ‘62, gives it to an officer in ‘63, and the embassy then turns against him as does the consulate because he's a Commie. “Well, they don't know what the hell they’re talking about—most of them. But they're not communists. What they want to do is improve the plight of the poor.” He'd been mayor of Recife. He’d been governor of Recife. He was one of the few people who did things. He had cultural programs, which the elites never did. He had all kinds of programs,

HANNAH: And even people who don't have a deep familiarity with Brazil are kind of vaguely aware of the country being home to real disparities between rich and poor. This is a country historically that has been—

ROETT: Inequality.

HANNAH: —Deep, deep inequality.

ROETT: One of the great anecdotes is the great medical doctor, Dr. Ibe—he mostly spoke in four-letter words, and we became friendly for various reasons. He said, “Yeah, we just brought in a bunch of ambulances.”

And I said, “Well, that's good, isn't it?”

“No,” he said, “What I need is hot water and soap in the interior of Brazil. You realize the roads are unpaved. What am I going to do with ambulances? We don't have technicians to maintain the ambulances.” But Washington said people must need ambulances. Well, Washington didn’t know what they were doing, either. We spent millions of dollars on things like ambulances and salaries and housing and stuff for people who didn't know what they were all about, unfortunately.

HANNAH: Washington's aid efforts and interventions during the 1960s and ‘70s weren't unique to Brazil. They were part of a larger American strategy to prevent the spread of communism in countries throughout South and Central America. So, in response to communist leader Fidel Castro's rise to power in Cuba in 1959, President John Kennedy called for the creation of an Alliance of Progress in 1961 to improve literacy and fight hunger and poverty in hopes of making countries in the region more resistant to communist forces.

Interlude featuring archival audio

ROETT: The US had great hopes of Brazil in 1961-‘62 when John F. Kennedy came in. We had the Alliance of Progress, and they opened the largest Alliance of Progress office in the world in Recife. And we were going to save the northeast of Brazil. I told them, “You aren't going to save the northeast of Brazil.” They didn't listen to me.

HANNAH: In 1961, the same year the Alliance of Progress began, Riordan was stationed in northeast Brazil in the city of Recife as a young Fulbright scholar. It was there Riordan gained insight into the forces at play—the forces which led to the US-backed military coup d'etat in 1964.

Interlude featuring archival audio

HANNAH: The United States paid close attention to Brazil's northeast region—where Riordan worked—since it was one of the poorest regions in South America, a region the US thought would be sympathetic to leftist political forces.

ROETT: More importantly, from a US point of view, the reporting from the embassy in Rio—but the real action was taking place in the Northeast, where I was—was increasingly alarming, and I always thought it was over-alarming. I told Lincoln Gordon, the ambassador, what I thought. I didn't see the secret memos, obviously, but I thought the atmosphere was increasingly alarming at the embassy and in the consulate. And I was just “pooh poohed” as a young professional. I wasn't in the foreign service. What did I know about these things? It was clear from me from talking to my leftist friends that things were coming to a head at some point. And Castelo Branco, who is a very pro-American Four-Star general—in fact he was a Marechal, a Marshall—and I had some conversations after the end of the English language prep lesson with his wife, and it was clear he was very—pro-American is the wrong term. He was very pro-democracy, and if Brazil and America could be on the same side, he supported that.. Unfortunately he was forced out. They killed Castelo Blanco in the year after because he was probably going to come back if there was a need to bring somebody back if there was a crisis. And so he crashed in a little plane. Little plane crashes, as we know, often send a signal. So he was gone.

Costa e Silva—who I never met—I gather was a nice guy, but didn't what the hell he was doing. He was a very classic, traditional Brazilian military officer, very conservative. He, of course, had a stroke, it is said, after two years. And then, in came the hardliners. So, when I went back in ‘70, the hardliners were in control. But also at that time, the economy was going crazy. For the wealthy it was doing very well. And for Brazil in general, it was going very well. And Garrastazu Médici—the president in 1970—and his wife became very popular because the economy was booming again—upper middle class, upper class. Lower classes as usual, in Brazil, never do very well, save for a fleeting moment. I was caught in the vortex of an increasing anti-Americanism because the military were increasingly annoyed with our stance—or Carter’s stance—on human rights. And of course, we sent not Jimmy Carter, but Mrs. Carter, to lecture the military a year or two later, and that set very badly with the armed forces as well.

HANNAH: Was that humiliating?

ROETT: Oh, God.

Interlude featuring archival audio

ROETT: It was President Geisel who was a very staunch Protestant, the only Protestant president Brazil ever had, and a man, I think, of principle. I shook hands with him a couple times. But he was embarrassed in front of his military officers by this lady from Georgia who didn't speak Portuguese coming in to tell him what he should be doing with this country. And that's not quite the way you run diplomacy.

HANNAH: While there were no direct military confrontations between the United States and the Soviet Union, the Cold War was incredibly bloody in many parts of the world. It's not the sort of peaceful period some people romanticize historically. So, can you talk about that—about what the legacy of the Cold War is in South and Central America, specifically?

ROETT: Chile, Argentina? Desaparecidos? Thousands and thousands of people were disappeared—I always love that phrase: were disappeared—by the military regimes because they were communists. And we went along with that until very late in Latin America. I think, we just didn't notice it. I was in and out of Brasilia a lot during those years doing research and other stuff, and it always struck me that somehow the embassy just never quite understood what the dynamics on the ground were. The excuse was always: “They cut our budget.” OK, well get on your goddamn car and drive. They cut our budget. We don't have enough personnel. Our Portuguese isn't very good.

HANNAH: Just bureaucratic obstacle after—

ROETT: Bureaucratic bullshit all the time. Nice people. Decently educated young men and women. But they couldn't deal with the immensity of half a continent which was in upheaval. And the military who was going to win, the military thought.. And so, if you got in their way, you disappeared.

HANNAH: It seems to me that a lot of countries, when they want American support, might try to emulate the United States in selective ways, but not in others, like coming down hard on communists, but not, for example, elevating due process or other democratic processes or institutions, right? And the United States was okay with that, especially during the Cold War.

ROETT: Well the Brazilians were very smart because they would have elections, which they always won, but they could say to Washington, “You see, the elections work. People get elected —” They were very smart. The Brazilians, unlike the Chilean and the Argentinians and many other countries, didn’t close down institutions. They gutted them.

HANNAH: Interesting.

ROETT: I always thought that was—they were smart. And so the parliament was left but the parliament was gutted. There were parties. But, “I think we'll just reorganize the political parties,” they said, and get rid of it. They didn't say get rid of the communists or socialists, but they’d get rid of them. Papers got published, but editors understood if they wanted to publish the next day, the censor in the office was going to have to read the stuff that was going to be published. But the papers came out.

HANNAH: Right. And there was just enough criticism of certain types of things. It sounds like what's happening—well, I don't want to make the comparison to China—but there’s—

ROETT: Hungary. Poland.

HANNAH: Yeah, exactly. And Georgia just had elections and…

ROETT: In Brazil it was poco poco. If somebody stuck his head up, he lost his head. So, as time went on in the ‘60s, fewer people put their head up.

HANNAH: The U.S.-backed coup, or what is known in Brazil as the coup of ‘64, led to a brutal military dictatorship, which lasted for 21 years until 1985. The constitution Brazil relies on today was formally enacted in 1988, which marked Brazil's turn from a military regime to a democracy.

ROETT: But what happened and after the restoration of civilian government rather than calling it democracy in the early ‘90s, is people like Cardoso and others really did help reestablish, in many ways, some of the institutions of democracy. Not all. And some of them were not well-founded, but they functioned. And what is still functioning today is the court system. It is a relatively robust, independent court system. But going back to Brazil, Cardoso, in a very brief period of democracy from ‘90 to the mid-1990s, was able to basically reinforce the rule of law, the court system, stabilize, more or less, a competitive political party system, and dealt with the greatest problem, which was inflation. I think Cardoso was the greatest president in Brazilian history. Others do not. He still, of course, is very much alive and intelligently commenting on things. But after he goes, there's no one really to take his place. And then came the populists.

HANNAH: One of the more well-known populist leaders was Luis Inacio Lula da Silva. Lula was president of Brazil from 2003 to 2010 and was a founding member of the Workers Party. Many attribute his rise to trade liberalization, which began in the 1990s and led to greater economic inequality and austerity, a trend many attribute to the rise of Brazil's current President Jair Bolsonaro.

ROETT: I had a center for Brazilian studies for a few years at SAIS, and we decided to invite Lula. He was coming to Washington to meet with someone—who knows. I wasn't in the State Department. I said, “Let's invite Lula to come and speak.” So, I pleaded with the dean, and he said, “Yeah, who is Lula? Oh yeah, that’s fine.”

HANNAH: Ah, Deans. It's such an easy target.

ROETT: Then we found out—we made contacts, and his people said he'd come to speak, and that we'll have an audience. I thought it would be mostly students. I didn’t know there would be activists––. Anyway, then we call the embassy as a courtesy. I said, “Mr. Lula's coming to speak.”

And it was absolute silence. And they said, “at SAIS?.”

And I said, “Yes.”

“Well, the ambassador can't attend.”

HANNAH: This is the Brazilian embassy to the U.S.?

ROETT: Yeah

HANNAH: OK.

ROETT: I said, “Well, I'm very sorry, but I wanted to extend the invitation.”

And again, “Thank you very much. Obrigada in Portuguese. Thank you for the invitation.”

So, Lulu shows up with an entourage. In those days he was a scruffy little fellow—nice smile, a lot of street smarts, I learned later. And he didn't have any schooling, but he had a sense that some of these populists just don't. What was going on around him—he could tell.

They brought him in. I didn't know what to call him. He’s not doutore's not a Senador, he’s not a presidente yet. He's just Lula.

Section containing portuguese.

So I said, “Boa noite, Senhor Lula.”

He said, “Oi Professor!”

He knew I was a professor. He said, “How are you?”

And I said, “I’m fine, Mr. Lula.”

He said, “You know Brazil, I understand.”

Section containing portuguese.

I never got to discuss Brazil. And he gave this crazy speech—if I didn't have tenure, they may have fired me—about imperialism and capitalism and social identity and the poor. All good stuff. And so, we got to the Q&A period, and I thought, “This is going to be fun.” And people were screaming and yelling, “fasciste! Communiste!” And I thought, “The dean must enjoy this.” So finally, I asked him a few questions about what he thought the Workers Party would do if they were elected to office. In a somewhat bombastic fashion, he said, “Change Brazil.”

“How's that possible?”

Section containing portuguese.

I thought, “No, you're not.”

Section containing portuguese.

And I said, “Yeah, you don’t know a thing about economics, buddy.” And then I asked him about the United States, and he said, “Professor, você é imperialista…" Section containing portuguese. What do you say to that?”

I can't remember what I said. I'm usually lost for words. In some ways I agree with him, but I can't say that.

HANNAH: You're used to American politicians who have a little bit of a better bedside manner, not just completely insulting your country.

ROETT: Lula didn't have much education. His family lived in one room behind a bar, and he had to use the bar's bathroom as he was growing up. This is someone that none of the people in the room could identify with.

HANNAH: And before long, he was running the largest economy in Latin America. How did he do, in your mind?

ROETT: The first four years were quite good. They had section containing portuguese with which they actually got money into the hands of poor people. And someone made a very strategic decision—I have no idea whom—to make sure the money got to the mothers in the family, not the fathers. On one of my trips to Brazil, I said, “Why did you decide that?”

Section containing portuguese.

He said, “If we give it to the men they're going to drink. Give it to the women, and they're going to buy milk.” I thought, “very smart.”

They had a number of other poverty reducing programs they put into place that were very effective. The difficulty in Latin America is that not all, but many, of the politicians are not well-educated, and they see an opportunity as money flows. This is the problem with Bolsonaro. And—I don't think Lula—but the people in Lula's government, in the second term began to say, “Wow, look at these billions. They love us.”

HANNAH: And that was ultimately his downfall.

ROETT: Yes, it was his downfall. Obama said, “Lula is my man.” It was at some international meeting—I don’t know what it was. And poor Lula, I think, was a limited person. He was a good person, I think. And in a different Brazil or in a different country, he probably would've been a fairly successful president. He still is. I think he'll win next year. Well, against Bolsonaro, I'd probably win. But it was like Allende. Not as bad. Allende meant well. He wanted to do good. Lula wanted to do good. But the difficulty with these populists when they come to power is they don't have the instruments at hand, and they're coming into a power structure they don't understand and which is resilient—very resilient.

HANNAH: Turning to the present moment, Riordan argues that America's major concern in the region now is migration. Of course, he's referring to the surge in people coming from Central America who are fleeing mass violence and poverty and traveling north to the United States-Mexico border. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, more than two million people are estimated to have left El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras since 2014.

ROETT: And the biggest problem we have is the border. And the border is—I was on some program with a member of Congress—administration was proposing four billion dollars for the border. I said, “Congress, vote against it.”

They said, “Professor, I can’t vote against four billion dollars for the border.”

“Oh yes, you can, because it's going to go down into the pockets of the drug lords and the extremely corrupt politicians who are in bed with the drug lords.”

He said, “Are you sure?”

I said, “Congressman, cross my heart. Believe me. That's what's going to happen.”

That was the Biden Administration’s, so far, major initiative—four billion dollars for the triangle. The triangle are the three small Central American countries—Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. They're just drug-ridden.

HANNAH: And that's where most of the money goes, where most of the migrants come up through Mexico, through the U.S.-Mexican border.

ROETT: I lectured the poor Congressman. “If you thought, Mr. Congressman, those four billion dollars are going to go into public schools, into public clinics, into road building, to farmers to get their products to the market, controlling the drug lords and the gangs, I’d say, go for it.”

Silence. He said, “I can't guarantee that, professor.”

I said, “Well.”

HANNAH: From throwing money at Brazil in the early 1960s in order to counter communism to investing billions of dollars into fighting the root causes of migration in Central America, is the United States getting it right with its policies in Central and South America?

ROETT: We're back to Afghanistan. We're back to Vietnam. Once we leave—and we're going to leave—what’ll happen is what happened in Vietnam in Saigon, what's happening in Kabul, what happened in Iraq. Once we go, everything goes back to what it was, but in a worse shade of what it was, unfortunately. That's the problem. Our problem is we think we can shove democracy down people's throats, and that's a glorious trait of both parties. And I think some people in the parties actually believe it. But it’s never worked. What you have to do is work from the grassroots up, and the United States is not very good at grassroots development. We think we are, but we don't hang on long enough. It's like Central America. If the congressman really believed me, which I don't think he did, the place you start is with public schools, public hospitals. We can't do that because we have to work through the bureaucracy in the country. And that's where the money disappears. So, the schools never get built. Hospitals don't get built. Roads don’t get paved. And people begin heading for the border.

HANNAH: According to Riordan, we haven't yet turned the page or learned the right lessons from past policy failures. So, what can we do instead? If military and economic interventions aren't working, what other solutions does America have to help improve the conditions and the relations in Latin America?

ROETT: Culture is important. We cut back on our cultural exchanges with Latin America, and the Chinese have filled that space. Young Latinos love American culture. We stopped sending the American symphony and dance companies. Decades and decades ago, some idiot somewhere decided it was useless to send. They were very popular, very popular. And so, the vacuum is filled. We cut back on the number of Fulbrights going down. Say what you want about Fulbright students—

HANNAH: Of which you are a product of the Fulbright program.

ROETT: I was one. A small number of people learn things about the country to which they're sent and then use it afterward. I think, which I did in my teaching and writing and lecturing, etc. But not enough.

So, they cut that back. And then during the Trump Administration—a lot of my colleagues are students—just left the Foreign Service who knew something about Latin America. So, Biden's challenge or Blinken's challenge—God help them—is to rebuild a foreign service. But you can't do that overnight. People have gone on to other jobs. And besides, the Congress isn't helping. Ambassadors aren't being improved. Mr. Cruz doesn't believe in the U.S. ambassadors unless they deal with the Nord Stream pipeline—which they can't do anything. So, the best we can do, it seems to me, is to maintain good diplomatic relations. I would increase the Fulbright program, not bringing Latin Americans up here, but bringing Americans down there—and this is all pie in the sky. I would re-institute the cultural exchange programs, because they're inexpensive, but they're very visible.

HANNAH: It is diplomacy and cultural exchange that the United States should be investing more heavily in, according to Riordan. With China's inroads in Latin America becoming the region's largest trading partner, it will be important to watch how the Biden Administration responds and what tools they use to engage the region.

Riordan Roett, thank you so much for joining us.

I'm Mark Hannah, and this has been another episode of None of the Above, a podcast of the Eurasia Group Foundation. I want to give a special thanks to our None of the Above team who make all of this possible. Thank you to our producer, Caroline Gray, our associate producer and editor Luke Taylor, and our music and mixing was done by Zubin Hensler. If you enjoyed what you've heard, we would appreciate you subscribing on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or anywhere else you find podcasts. Rate and review us. If there is a topic you want us to cover, shoot us an email at info@noneoftheabovepodcast.org. Thanks for joining. Stay safe. See you next time!